A Christian Counselor on Co-narrating: Helping Teen Sons (and Fathers) to Tell Their Stories

Chris Lewis

Part 1 of a 4-Part Series

This series offers personal reflections and therapeutic perspectives related to Dr. William Pollack’s book “Real Boys,” on engaging the hearts of young men who are confronted with the shame-hardening effects of “the Boy Code.” This first part which follows is a narrative prelude.

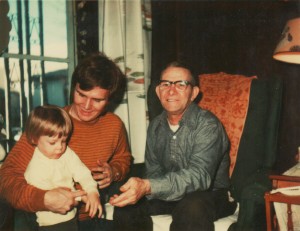

Pap, Dad and the author as a boy on a visit to Allentown.

Pap, Dad and the author as a boy on a visit to Allentown.In graduate school I had a psychology professor, Dr. Dan Allender, who uttered a truth that is still settling into my pores: “I don’t trust a man until I know his tragedy.”

My professor’s trust was really rooted in the man himself knowing his own tragedy. Not simply a head-knowledge recitation of tragic events, but the kind of grieving and self-awakening that allows a man to embrace and to share the whole of his experience, its inherent beauty and debris and mystery, so that he can actually articulate his story to himself and to others.

This is how people change. This is the work of counseling, especially Christian counseling, the work of learning to read your own life-text. It is also the Christian narrative that we are all caught up in: the terror and sorrow and joy of being known, of falling hard into self-discovery. Healing in the wilderness. Belonging and redemption.

Masculine Trauma: A Loss for Words

I’ve only a vague sketch of him, but I don’t doubt that underneath it all, my grandfather “Pap” was a “good man,” as the Allentown song lyrics go. What “keeps a good man down” is when he doesn’t know this in his own heart.

Long before his wounding on the German front, Pap bore a far deeper scar that I imagine never healed: Pap’s temper reminded relatives of his own father, Stanley, who’d died at age 43, before my Dad was born. Stanley is a forgotten man. Pap never talked about him with my Dad – nobody did – even though he’d lived a block away, where Dad still visited grandma as a boy.

Pap’s pained family silence, and the muted horror of war, point to a more profoundtragedy – Pap’s inability to connect with and tell his story. In his shame and isolation, Pap could not narrate a fuller, more emotionally attuned image of masculinity to my Dad. He did not have the words.

Two points need to be made here:

- This emotional, narrative disconnect is evidence of trauma, a bell tolling on the battlefield of a broken mind, in which a man is cut off from his sense of self.

- Such trauma cannot be minimized as belonging to a certain bygone era or generation (or gender) – or even to war itself. Both trauma and parent-child attachment research point to the potential mental health issues that can emerge when a child is raised in an emotionally volatile or detached environment, being exposed to a kind of chronic, cumulative developmental trauma that can be just as debilitating as war.

Tragedy and Trust

Boys begin to piece together an identity from the stories passed down by other men – whether by their presence or their absence. This absence can be physical or emotional, weaving shadows of doubt into a generational story.

Because pieces of Pap’s emotional life went “missing,” my Dad and I lost a certain “felt sense” of ourselves. We lost the grounded security of knowing and naming where we came from. People move on, but they carry a hole of not-knowing. Even in connected father-son relationships, unspoken relational “gaps” from a father’s past can affect his ability to “co-narrate” his son’s story if they limit emotional access to himself.

A boy learns to find, trust, and tell his own story based on co-narrating experiences with older men. Especially when his elders can honestly engage their tragedies, failures, and father-wounds. Otherwise men risk bequeathing to boys the shame of their own unresolved loss.

Past and Present

Attachment research shows not only that fathers have the same biological capacity for emotional bonding as mothers, but also this: that a father’s growing self-awareness and understanding of his life story – how his own family history has influenced his fathering, leading him to make adjustments – is the single most important variable in parental effectiveness and a child’s emotional health.

What blocks the co-narrating connection between men and boys, in particular, are the media stereotyped images of masculinity – the myths and mixed messages that have been codified, handed down, and re-enacted in culturally insidious ways.

Masking Shame: Looking Behind the Behavior

Pap holding his grandson, the author.

Pap holding his grandson, the author.Psychologist William Pollack calls it the “Boy Code” – those constricting, archaic assumptions about manhood that society has used since the 1800s to define and socialize boys. In his book Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myths of Boyhood, Pollack outlines how this caricature of masculinity – the machismo and false bravado of the old Boy Code – continues to shame boys into constructing a mask of coolly tough competence that ultimately cuts them off from their true feelings and genuine relationships with others. “I’m fine. It’s all good. I can handle it.”

Pollack identifies two hallmarks of the “Boy Code” that stymie emotional development:

- The subtle but pervasive ‘toughening-up’ process that shames a boy for feeling vulnerable or needy

- The premature separation from emotional family bonding that pushes a pseudo-independence on a boy , even in supportive but unsuspecting families

Boys entering adolescence encounter a host of external performance pressures, biochemical changes, and distorted male role models. This can generate a protective, shame-based ambivalence about becoming a man – and a terrifying retreat behind the mask.

Faced with this mask, we see the behavior but miss the boy – until his withdrawal or hyper-activity slides into defiance, rage, apathy, depression, academic struggles, or substance abuse. His symptomatic behavior may be punished or simply interpreted as a “guy thing,” but inwardly, in this fog-of-war experience, a boy is desperately seeking the face of a co-narrator.

Christian Counseling: From Saving To Finding Face

As a Christian counselor, I work with boys and teens who are acting out a timeless Boy-Code drama in which the family bond becomes a bind: a bind of wanting to stay close, but needing to ‘save face.’ Professional Christian counseling gives a boy time and space to find his real face – and hopefully the face of other men in his life.

Counseling helps a boy to narrate his story in his own words, with his own voice – but not on his own.

Pollack, W. (1998).Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myths of Boyhood. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.Photos courtesy of author’s family.